The Atlas-I Trestle at

Kirtland Air Force Base

Story by Charles Reuben

shawnee@unm.edu

Read the published version of the story by clicking this sentence.

Question: What New Mexico structure is 12 stories tall, built entirely out of wood and helped win the Cold War? (Hint: It is NOT the “Rattler” rollercoaster at  Uncle Cliff’s Amusement Park.)

Uncle Cliff’s Amusement Park.)

Answer: “The Trestle” at Kirtland Air Force Base.

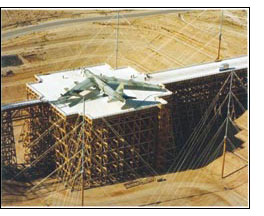

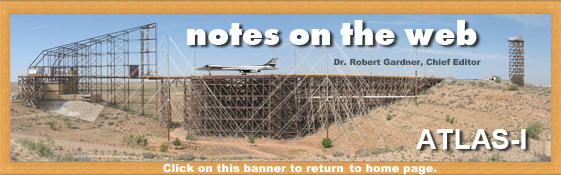

The Trestle at Kirtland Air Force Base supports a wooden runway that faces an arsenal of spotlights and rusting signal-generating equipment that have not been turned on in over 20 years.

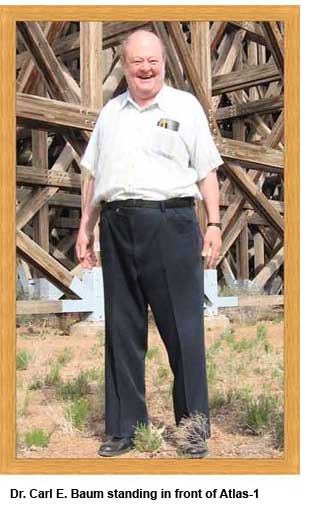

The Trestle, or “ATLAS-I” (short for Air Force Weapons Lab Transmission-Line Aircraft Simulator) was the brainchild of my boss, Dr. Carl E. Baum, who worked at the Base for 42 years and is now a Distinguished Research Professor at The University of New Mexico. The Trestle, inspired by a railroad bridge, is a test stand for the world’s largest electromagnetic pulse simulator. It is two football fields long and was built over an enormous, bowl-shaped arroyo, deep inside this high-security military complex.

Between 1980 and 1990, military aircraft were towed onto the deck of this wooden mesa and bombarded with electromagnetic pulses, or “EMP,” like the kind madeby an exploding nuclear bomb. The purpose of these classified experiments was to measure the effects of these electromagnetic waves on the delicate electronics and soft underbelly of military aircraft.

Atomic tests like these used to be conducted in a grand, theatrical style during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, a time when military money flowed like water. It was the ultimate “Reality Show”: If you want to see how a 100 ton, 185 ft.-wide B-52 Bomber was affected by an H-Bomb, you simply wheeled the plane onto the Trestle’s deck, charged up its Marx capacitors with 0.2 terawatts of electricity (that’s 10 to the 12th watts), aimed, and fired.

“That’s only a tiny percentage of a nuclear weapon but it’s a lot of energy for a short period of time in a limited space,” Baum said.

“Instead of detonating a nuclear bomb to produce an EMP (electromagnetic pulse) covering the continent, we produced similar fields over a smaller region of space. The total energy produced was about 200 kilojoules. Human beings are essentially not affected by this, only the electronics.”

Baum said that the testing of delicate and complex electronics is no longer done this way. Mathematical simulations are now conducted by powerful supercomputers in order to save money, but he isn’t impressed. “Part of the problem with mathematical simulations is that the systems of interest are extremely complex. There is even variation between two copies of the same system.”

Baum said that the testing of delicate and complex electronics is no longer done this way. Mathematical simulations are now conducted by powerful supercomputers in order to save money, but he isn’t impressed. “Part of the problem with mathematical simulations is that the systems of interest are extremely complex. There is even variation between two copies of the same system.”

Baum does not use a computer at work.

“I have more important things to do than worry about computer maintenance or spending my time typing things into a computer . . . especially mathematical things. That was my employment agreement with the Air Force and part of my employment agreement here at UNM.”

Baum prefers to use what he calls a “graphite composite symbolic manipulator” (a pencil) and three-lined punched paper to record his ideas. When he lectures at conferences and great universities around the world, he insists that an old-fashioned viewgraph be ready and waiting for him to display his transparencies of colorful, hand-drawn notes. When he needs to type an abstract or read and respond to his e-mail, he calls upon yours truly.

Baum, 67, retired from the Air Force in 2005 and was recently aw arded the highest honor given in the field of electromagnetics. He also holds the position of “Distinguished Research Professor” at the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at the University of New Mexico. He is one of the most sought-after experts in the field of electromagnetics whose single-spaced biography is over 30 pages long.

arded the highest honor given in the field of electromagnetics. He also holds the position of “Distinguished Research Professor” at the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department at the University of New Mexico. He is one of the most sought-after experts in the field of electromagnetics whose single-spaced biography is over 30 pages long.

Baum arrives to work every day in his un-air-conditioned 1962 white Chevrolet Corvair. He bought the car brand new during his student days at Caltech and proudly refers to it as “basic transportation.” The car has logged over 160,000 miles and no longer has a radio.

Baum spends his days at UNM writing and reviewing technical papers and advising graduate students in a large office neatly crammed with aisles of books, and walls covered with plaques, awards, framed letters and gifts. Buried two stories below the earth’s surface, Baum is glad to have found a friendly place to conduct his research and draws no university salary,  having earned a generous civil-service pension in the Air Force.

having earned a generous civil-service pension in the Air Force.

When he isn’t busy working on his research, Baum writes classical music. He has written 14 choral arrangements, three sonatas, four quintets, two quartets, two fanfares and a march. He often teams up with professors and graduate students at UNM’s music department, as well as other local musicians.

And when he isn’t busy writing music, he acts as head of the Summa Foundation, a philanthropic organization that encourages students to study electromagnetics.

Baum reflected on the necessity of building the $60 million Trestle, both symbolically and practically. He explained that if an atomic bomb was detonated a couple hundred miles over the United States, the EMP that was produced could wipe out our computers, our entire electrical power grid, our telecommunications infrastructure and our satellites.

“The Nuclear EMP was an important technical problem during the Cold War because it was vital that the Soviets could not attack an EMP Achilles’ heel. Testing of the strategic systems was important to convince them of this fact.”

“The Nuclear EMP was an important technical problem during the Cold War because it was vital that the Soviets could not attack an EMP Achilles’ heel. Testing of the strategic systems was important to convince them of this fact.”

Evidently the Russians were impressed.

In 1996, at the AMEREM symposium in Albuquerque, the renowned General Major Vladimir Loborev, visited the Trestle site. He thought it was a wonderful facility and, through his translator, told Baum “you must realize that if it were not for us, you would have never built this.”

Baum replied, “Yes sir . . . thank you, sir,” and shook his hand.

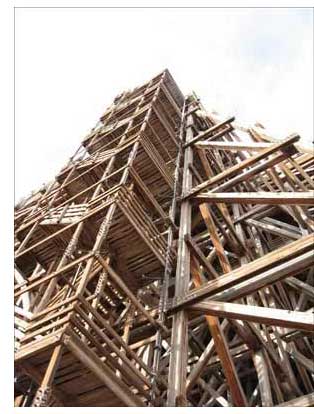

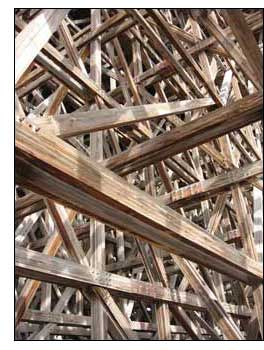

The Kirtland Trestle was constructed using very little metal; even the bolts holding it together were made of wood or fiberglass. By constructing the Trestle in such a manner, its platform, rising 115 feet above the desert floor, was almost invisible to the electromagnetic waves being shot at it and simulated an aircraft in flight.

“It is reputed to have taken one or two months of the national lumber output from the Northwest and Georgia to make the glue-laminated structural members,” said Baum about his southern pine and douglas fir Trestle. “You don’t look at it,” he said laughing: “It looks at you!”

Mark A. Miller, a professional engineer who worked on the project said,

I designed most of the wooden structure as a junior engineer at Krause Engineering in Santa Fe. We were working for the architect in Albuquerque; the prime contractor was McDonald-Douglas. I spent most of the first two years of my career working on it.

The resin-impregnated wooden bolts were . . . furniture quality items. We could use no piece of metal longer than 12” , and the columns were 12” x 12” with 6” pieces bolted on both sides, so the minimum bolt grip was 24”, which pretty much precluded metal bolts . . .

The design work was done in 1973-1975, and I recall that people were amused by the required environmental impact study, which concluded that some rabbits and a few horned toads might be displaced by the project.

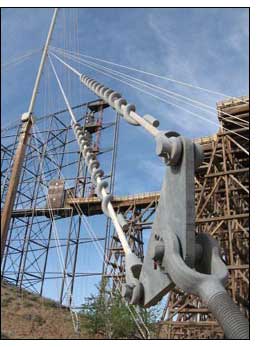

The steel wave focusing structure was designed by Jim Hands, the chief engineer in the office, and it was the tallest structure in Albuquerque at the time . . . It was quite a project, with calculations filling dozens of ring binders.

The structure is in great shape for a piece of engineering that has not been maintained in 20 years. When funding for the project stopped, everybody was told to pack up and leave immediately: Half-drunk cups of coffee and sandwiches were left behind.

Surrounded by two fences and a motorized gate, you will end up in a military jail (or shot) if you try to approach the Trestle without an invitation. Visitors must get permission from the Base commander and undergo a background check if they want to visit.

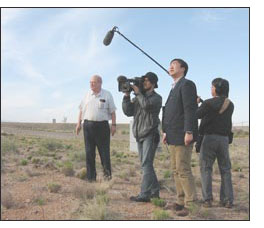

Since 9/11, tours have become even more restricted. The only reason that I got to see it was because I was tagging along for the ride: A Japanese  film crew was making a documentary about the Cold War and wanted to interview my boss at the site.

film crew was making a documentary about the Cold War and wanted to interview my boss at the site.

About the only people who use the Trestle now, with any regularity, are soldiers from the Army division who like to rappel from its intricate structure, and “Big Crow,” a military organization that uses its offices and act as its caretakers.

The structure is a home for bobcats, crows, owls and red-tailed hawks. Like many military and Air Force institutions (Vandenberg Air Force Base comes to mind), this area is slowly becoming reclaimed by nature.

Even Hollywood has been barred from making action/adventure movies on the site, although Dr. Baum readily admits it would be perfect for such a use and he seems to have a screenplay tucked away in his back pocket.

“It would be an ideal site for a James Bond movie set in the waning days of the Cold War entitled, Empire My Prince,” mused Baum.

Baum said that the title of his movie has a double meaning. The Initials of “Empire My Prince” are “EMP,” as are the first three letters of the word “Empire.” EMP, we recall, is shorthand for “Electromagnetic Pulse.”

“My film concerns a British EMP bomb which, of course, has to travel to the Nevada Test Site for testing, with various adventures occurring along the journey,“ Baum said coyly.

These days Baum’s research is focused on killing cancer cells. He is also involved in trying to figure out a way to detonate IEDs (improvised explosive devices) on the side of the roads in Iraq, before they kill or maim our troops.

on the side of the roads in Iraq, before they kill or maim our troops.

Such systems are known as “non-lethal weapon systems” or “counter-lethal” in the sense that they prevent people from dying.

Albuquerque has a bad track record when it comes to preserving its history. What hasn’t burned down has been torn down and what hasn’t been torn down is falling into decay, like the locomotive repair center near downtown.

Similarly the Kirtland Trestle has the potential of becoming a decaying ghost town (or a spectacular, 6.5-million-board-feet “Baum fire”) if somebody from the State’s Historical Division doesn’t step in soon and put it on the National Register for Historic Places.

Indeed, now that the fire suppression system has been disconnected, a blazing inferno is always a possibility.

“That’s the only way to get rid of it,” Baum said quietly.

The Base is planning to make the Trestle “all but” a National Historic Site. The problem is that if you make it a national historic site there are issues about maintaining it, and that costs money.

Meanwhile, “the Trestle is visible from the air if your plane takes off or lands in the proper direction,” said Baum. Also, the Trestle can be clearly seen from the space shuttle or the International Space Station, if you have the right telescope.

On the bright side, a DVD is in preparation for the National Atomic Museum. It is undergoing review for public release and is chock full of archival footage, interviews and eye-popping simulations.

Unfortunately this might not be good enough for people who want to see this structure in person, especially those who might regard this marvel of engineering as “art.”

“And what a beautiful piece of art that trestle is!" said Dr. Selma Holo, director of the Fisher Gallery at the University of Southern California. "The details of that wooden trestle remind me of the wonderful abstract art that assemblage artists can only dream of making!"

“And what a beautiful piece of art that trestle is!" said Dr. Selma Holo, director of the Fisher Gallery at the University of Southern California. "The details of that wooden trestle remind me of the wonderful abstract art that assemblage artists can only dream of making!"

The Kirtland Trestle, even after 20 years of abandonment, is in very good shape but it does need to be preserved for future generations who might someday get access to the Base.

Who knows, there may come a time when it will be regarded as a prime location to watch fireworks on the 4th of July, a spectacular place to see Flamenco dancers strut their stuff, or simply a piece of “installation art,” right up there with the Eiffel Tower!

In the meantime, Dr. Baum doesn’t have to worry about whether an unexpected EMP blast will disrupt his diligent, safe, daily commute to work at UNM. After all, he drives a ’62 Corvair which lacks any computerized parts that could be destroyed by the EMP of an exploding nuclear bomb.

Typos? Corrections? Suggestions? Contact Webmaster Here!

Copyright © 2012 Electrical and Computer Engineering Department

The University of New Mexico, All rights reserved